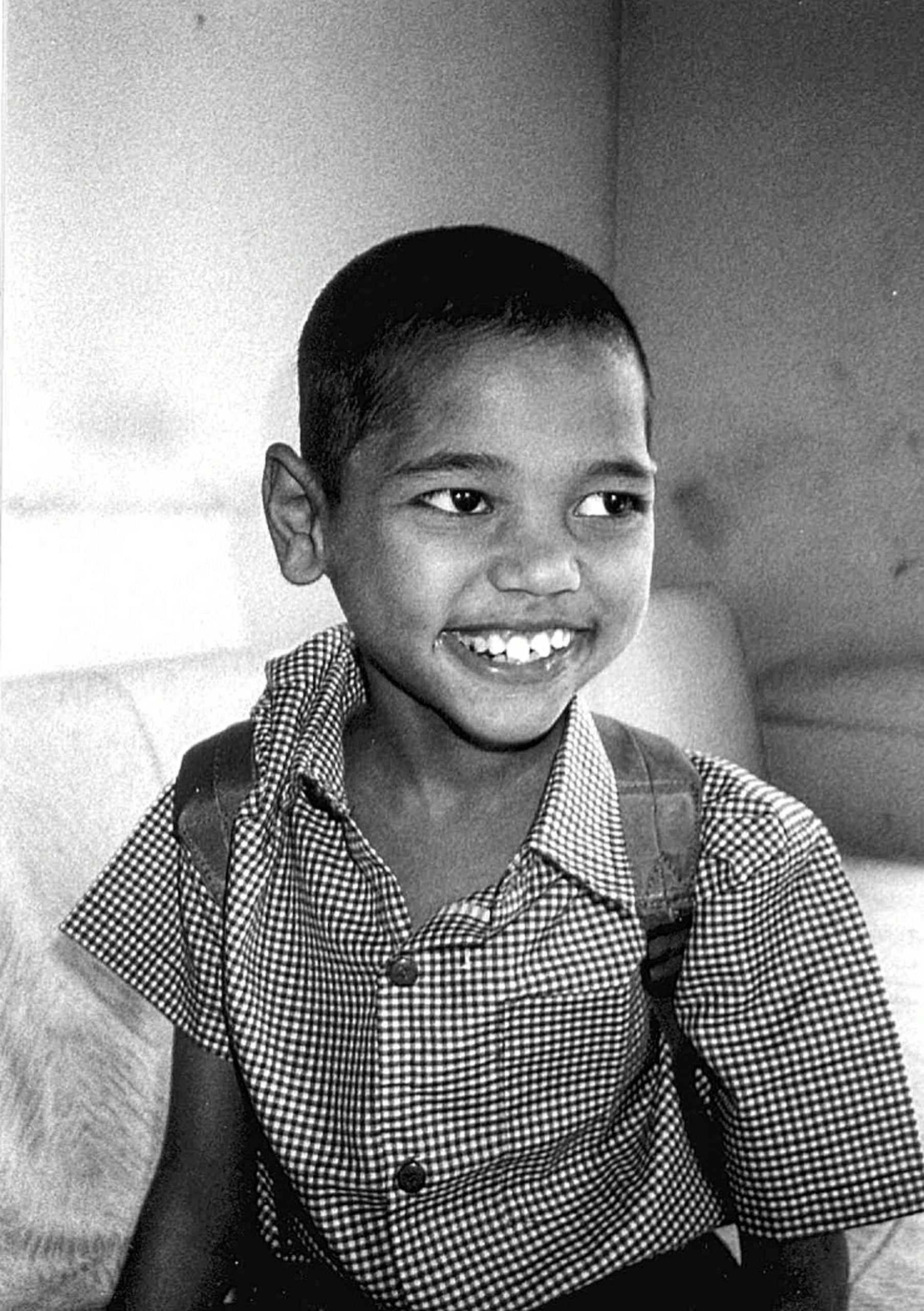

In 1999 the first children at the Apanjan Project in Calcutta were Prem, Raju and Ajay. It was 8 year old Raju who proved by far the most difficult child. Assessments were never quite accurate, his needs however crystal clear. That he hovered somewhere on the autistic spectrum was obvious, but his ability to connect, albeit on his own terms, was unusual and therefore it was decided that Raju was just Raju. At Apanjan the child thrived, always the centre of attention, his unbridled happiness infected every visitor and nobody got away without a friendly push and a smack. He never learned how to talk, he simply expressed no interest in words. The language was in his piercing eyes and they could speak volumes. We knew Raju was happy at Apanjan, he never hesitated to show us. A structured life of daily routines suited him well; he felt safe and loved and most importantly, Raju was allowed to be himself. Of course we harboured the hope that one day he would be able to tell us his real name, but Raju died far too young. In 2013 he did not survive a severe epileptic seizure. Everybody at Apanjan and the Banyan Trust was completely crushed. A light went out at Apanjan, forever.

Month: March 2021

ARTI

Arti was ten years old when she arrived at Apanjan, where she was lovingly accepted into the small community of children with special needs and their group of excellent carers. Due to strict legal gender rules, the project could only still accommodate boys. For the moment, Arti could stay within the compound with a carer. There were plans for a girls home, an adjacent plot had just gone up for sale, fundraising strategies were being deliberated, but it was really Arti’s unexpected arrival that gave it the final push. In the UK an anonymous donor provided the funds for the plot, in the Netherlands a generous family offered to pay for the building and its refurbishment. Soon Arti was watching her new home being built.

Arti was deaf-mute and being an expressive girl, she needed sign language lessons. A sign language educator was brought in to teach at the Day Centre. All staff participated in the lessons that came to benefit dozens of students at Apanjan in the years following. But most importantly, finally Arti was able to tell us her story:

She had lost her parents in the chaos of Sealdah Station, in the endless stream of migrants from the countryside that pour into Calcutta in search of a better life. Wandering the hostile city streets in despair, the girl joined a gang of street-children that tried to survive together.

One night the group was approached by a policeman. All other children scattered, but not Arti who saw in him an opportunity for help to find her family. The policeman clocking that the girl was deaf-mute gestured her to follow him.

Suddenly he grabbed her by the neck and arm, she tried to wriggle free, but the man was strong and slapped her very hard. He managed to drag her into a dark alleyway, where he violently raped the ten year old girl and beat her until she lost consciousness.

That’s how Arti was found. People immediately contacted OFFER, the local NGO that looks after street-children. OFFER staff took her to the hospital, where she was examined and treated for her injuries, and after discharge they knew they had to find this vulnerable girl a shelter, a safe home. And what better place than Apanjan in sleepy Govindapur?

At Apanjan the carers looked after the deeply traumatised girl with a tenderness she had never known. Arti needed to learn to trust people again, remember how to be a ten year old girl, to realise that she was safe and that she had found a new home. More girls joined her at the new home and she happily grew into her role as eldest sister. Although without doubt deeply damaged by what had happened to her, it did not take long before she no longer showed it. A very bright girl, Arti was always cheerful, had a great sense of humour, was caring and she rapidly became indispensable within the Apanjan community.

It took about two years before we could come to the cautious conclusion that thanks to all the right therapy, intensive guidance and the loving environment Arti had found enough inner peace. This lovely girl had resolutely closed a dark chapter and begun, with great eagerness, to live the rest of her life.

LITON

Liton was amongst the first students at Sanjeevani. A withdrawn sixteen year old boy, he had Marfan’s Syndrome, a disorder that affects the connective tissue in many parts of the body, with unusually tall and thin limbs as its visible manifestation. Liton had heart problems, damaged organs, a compromised general health and also learning difficulties. Always bullied because of his appearance and a voice disorder, he tended to hide from people and hardly ever spoke. Liton had very loving parents who pleaded with Sanjeevani to give the boy a chance.

He was put in a group of older children and immediately took an interest in all the teaching aids and educational toys around him. Sanjeevani’s Montessori spirit allowed him his own pace and choices, gently coached by the special educators; first with puzzles and building games, later with group exercises, where he began to come out of his shell.

Liton did well at Sanjeevani. He made friends, hanging out together after school, he learned how to read and write and every day he insisted on singing the Bangladesh national anthem, chest puffed up with pride.

Liton had a peculiar obsession: the city of Sylhet in North Bangladesh. Every visitor at Sanjeevani was asked to enquire with Liton when he would go to Sylhet. An immediate ice-breaker, he would beam and squeak with excitement: “next week, by train!”. Until one day, when I as regular visitor asked that same routine question and a painful silence descended. Everybody looked at the floor. I was quickly ushered to a corner by head teacher Rabeya, where she whispered: “best to never mention Sylhet again. Liton went last weekend and he hated it. He’s devastated.”

The paradise of Liton’s dreams may not have existed in real life, but soon a dream did come true for his proud parents, when Liton had a lead role in a play on stage at a big conference about disability and poverty, organised in Dhaka by the Banyan Trust; full of confidence, funny and loving the applause, Liton showed to the world his remarkable transformation.

In 2014 the moment came that it was time for Liton to move on. He got a job helping out in a market stall, where he worked hard, even able to handle money. People liked being served by him, stopped to have a chat, everybody knew him. Liton finally belonged.

But his health did not get better. He had more and more trouble breathing and tired quickly. Doctors blamed Marfan’s Syndrome and explained that most probably his heart was elongating, stretched to capacity like an elastic. One evening Liton came home from work and complained he didn’t feel well. He went to bed early and never woke up.

In life Liton had arrived with such great disadvantages, but he left as a young man who had learned to find happiness in small things; a life truly worth living.